We schrijven het jaar 1994, het eerste Donner memorial Schaaktoernooi. Naast een tienkamp met Nederlandse toppers en enkele sterke buitenlandse grootmeesters was er een groep samengesteld met spelers die ooit tegen Donner hadden gespeeld. De knarrengroep schreef Jan Joost Lindner in De Volkskrant en Eric Lobron dacht dat hij naar Jurassic Park zat te kijken. Met deelnemers als Smyslov, Bronstein, Pachman, Unzicker, Velimirovic en Gligoric waande je je inderdaad in lang vergane tijden. Lindner schreef ook over de rustige golfslag van halve punten, maar er was zeker één speler die daar niet in meeging. De Joegoslavische grootmeester Svetozar Gligoric toonde zich allesbehalve vreedzaam met vier overwinningen, twee nederlagen en drie remises.

In de jaren vijftig en zestig, toen de Sovjetschakers de schaakwereld overheersten was Gligoric een van de weinigen uit andere landen die gelijke tred kon houden. Althans als het om toernooien en landenwedstrijden ging. In de strijd om de wereldtitel bracht hij het er een stuk minder af. Daarin kwam hij niet verder dan twee middelmatige resultaten in de kandidatentoernooien van 1953 en 1959 en een verloren kandidatentweekamp tegen Tal in 1968. Maar daarbuiten won hij talrijke toernooien, werd hij twaalf keer Joegoslavisch kampioen en speelde hij in de periode 1950-1982 vijftien keer mee in het Joegoslavische Olympiadeteam, waarvan dertien keer aan het eerste bord. Met 88 winstpartijen, 26 nederlagen en 109 remises is zijn Olympiadescore indrukwekkend.

Gligoric had een moeilijke start in het leven. Hij werd in 1923 geboren in armelijke omstandigheden, verloor zijn ouders al jong en maakte zelf zijn eerste schaakspel van kurken, zo is overal te lezen. Zijn talent was snel duidelijk maar de Tweede Wereldoorlog zorgde voor een onderbreking in zijn schaakontwikkeling. Gligoric vocht in het partizanenleger van maarschalk Tito tegen de Duitsers en bracht het tot kaptein. Er wordt wel gesuggereerd dat die onderbreking rond zijn twintigste fataal is geweest voor de stap naar de absolute top. Immers juist in die fase kan je als schaker snel groeien.

De oorlog lijkt geen negatieve invloed te hebben gehad op zijn karakter. Gligoric gold als een heer onder de schakers. Hij probeerde het spel objectief te benaderen, als een strijd tussen ideeën, niet tussen personen. Vandaar ook dat zijn autobiografie de titel I play against pieces meekreeg. In die strijd tegen de stukken was hij overigens buitengewoon creatief. Hij lanceerde flink wat openingsideeën, bijvoorbeeld in het Konings-Indisch, Spaans en Nimzo-Indisch.

In zijn latere jaren, toen hij wat minder vaak speelde maakte hij faam als schaakauteur en commentator. Zijn boek over de match Fischer-Spassky 1972 was al enkele dagen na het eind van de match klaar en bereikte een oplage van meer dan 400.000 exemplaren. Is dat ooit geëvenaard?

Toen Gligoric in 2012 overleed was hij in Servië, Joegoslavië was intussen ter ziele, nog steeds een grote naam. Hij werd begraven in de Laan van de Groten op het nieuwe kerkhof van Belgrado. Uit zijn laatste jaren liet hij iets bijzonders na. Een jaar voor zijn dood presenteerde hij een cd met composities van eigen hand. De plaat bevat jazz, blues, ballades en rap. Dat laatste had ik wel eens willen horen. De titel luidde: Kako Sam Preziveo Dvadeseti Vek, Hoe ik de twintigste eeuw overleefde. Enkele nummers zijn te vinden op YouTube. (MbdW)

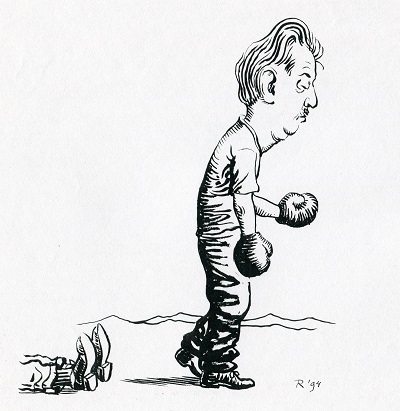

Gligoric, chess player and composer

We are in the year 1994 – the first Donner Memorial Chess Tournament. Besides a ten-player event with top Dutch players and several foreign grandmasters, a group was composed with players who had faced Donner at the board. The ‘old fogeys’ group’, Jan Joost Lindner called it in de Volkskrant, and Eric Lobron wondered if he was watching Jurassic Park. With participants like Vasily Smyslov, David Bronstein, Ludek Pachman, Wolfgang Unzicker, Draguljub Velimirovic and Svetozar Gligoric you might indeed imagine yourself in long bygone days. Lindner also wrote about the ‘quiet surge of half points’, but there was at least one player who didn’t go along with this. The Yugoslav grandmaster Svetozar Gligoric showed anything but peacefulness with four wins, two defeats and three draws.

In the 1950s and 1960s, when the Soviet players ruled the chess world, Gligoric was one of the few players from other countries who could keep pace with them – at least, when it came to tournaments and international team contests. In the struggle for the world title he didn’t do so well. He didn’t get any further than two mediocre results in the Candidates tournaments of 1953 and 1959, and a Candidates match he lost against Tal in 1968. But outside the cycle, he won countless tournaments, became Yugoslav champion twelve times, and in the period 1950-1982 participated in the Yugoslav Olympiad team fifteen times – of which thirteen times on first board. With 88 wins, 26 losses and 109 draws, his Olympiad score was impressive.

Gligoric had a tough start in his life. He was born in poverty in 1923, lost his parents at a young age, and made his own chess set from corks, as we can read everywhere. Soon it became clear that he was talented, but the Second World War interrupted his chess development. Gligoric fought against the Germans in Marshall Tito’s partisan army, and rose to the rank of captain. It has been suggested that this break around his twentieth year was fatal for his final step to the absolute top. After all, it is precisely in that age category when you can grow quickly as a chess player.

The war doesn’t seem to have had any negative influence on his character. Gligoric was known as a gentleman among chess players. He tried to approach the game objectively, as a struggle between ideas not persons. For that reason also, his autobiography got titled I play against pieces. In this battle against the pieces, by the way, he was extraordinarily creative. He launched quite a few opening ideas, for example in the King’s Indian, the Ruy Lopez and the Nimzo-Indian.

In his later years, when he started playing a little less frequently, he earned fame as a chess author and commentator. He finished his book on the 1972 Fischer-Spassky match a few days after the match, and it had a circulation of more than 400,000 copies. Has this ever been equalled?

When Gligoric passed away in 2012, he was still a big name in Serbia – Yugoslavia had been dismantled by this time. He was buried in the Alley of the Greats in Belgrade’s new cemetery. From his later years, he left something very special to prosperity. One year before his death, he brought out a CD with compositions by himself. The album contains jazz, blues, ballads, and rap. I would certainly like to hear some of his rap compositions. The album title was Kako Sam Preziveo Dvadeseti Vek (How I survived the twentieth century). Some of the songs can be found on YouTube. (MbdW)