Wanneer Sosonko op 18 augustus 1972 in het vliegtuig van Leningrad naar Wenen stapt, laat hij niet alleen Rusland achter zich maar ook een carrière als trainer van de allersterksten. Eerst staat hij Tal terzijde, later Kortsjnoi. Twee totaal verschillende persoonlijkheden, dat is zeker. Daar waar Sosonko aangaf enige moeite te hebben gehad het levensritme van Tal te volgen, bleven hij en Kortsjnoi elkaar gewoon met ‘u’ aanspreken! Hoe de samenwerking met de laatste verliep vertelt Genna later in De zuiverste liefde is die tussen een man en zijn paard: “In Rusland is het dan de gewoonte dat je je terugtrekt in een rusthuis. Je traint vier, vijf uur per dag en rust ontzettend veel. Op zichzelf is dat alles fantastisch geregeld.” Op een vraag van interviewer Max Pam of de treurigheid hem dan niet naar de keel slaat, antwoordt Sosonko: “Ach, wat zal ik zeggen. Het is hier nu eenmaal minder professioneel, maar dat is niet erg. Als individu heb je hier veel meer ruimte en ook in het Westen is het mogelijk een goede schaker te worden.”

Daarvan is Sosonko zelf een goed voorbeeld. Na zijn emigratie gaat hij eerst naar Israël, maar belandt al snel in Nederland, waar hij de vrouw van Ton Sijbrands kent. In Nederland rijgen toernooizeges zich aan elkaar en in 1973 wordt hij Nederlands kampioen – na een beslissingsdriekamp, dat wel. Het eerdere professionele werk legt geen windeieren. Zijn openingen hebben een bijzondere dynamiek: met zwart de Draak en de Ragozin. Zeer tactische openingen, en zeker niet elke witspeler durft de confrontatie aan. Dat is natuurlijk prima voor zwart… Over zijn witrepertoire zei Sosonko eens: “Ik kan bij zet drie op mijn notatiebiljet alvast 3. g3 invullen”. Behalve tegen het Konings- en Grünfeld-Indisch dan: daar koos hij voor klassieke opstellingen.

Genna had in Rusland de titel van Nationaal Meester behaald, maar die telt niet daarbuiten… In 1974 wordt hij IM, en in 1976 grootmeester. Dan begint een zeer succesvolle periode. Hij wint Hoogovens (1977, 1981), een tweede keer het NK (1978) en klimt naar de top twintig van de wereld. Dat blijkt ook zijn top: in de WK cycli plaatste hij zich twee keer voor een interzonaal toernooi: Biel 1976 en Tunis 1985. Het eerste kwam te vroeg, het tweede te laat zou je zeggen, al eindigde Genna in Tunis maar net buiten de kwalificatieplaatsen. Voor het Olympiadeteam verloor hij zeer zelden en ik vraag me af waar Genna zelf de voorkeur aangeeft: Haifa 1976 (zelf goud op bord 2, Nederland zilver) of Thessaloniki 1988 (playing captain, en brons). In 1976 deden er nogal wat landen niet mee, en het brons in 1988 was een complete verrassing.

De betekenis van Genna voor het Nederlandse schaak is moeilijk te overschatten. Als speler, trainer, bondscoach en schrijver heeft hij veel talenten hogerop gebracht. Terecht kreeg hij dan ook in 2007 de Max Euwe ring, die hij later in 2012 doorgaf aan een andere eminente bondscoach, Cor van Wijgerden. Nadat zijn actieve carrière geëindigd was, legde Genna zich toe op het schrijven over het verleden van Russische schakers. Drie delen zijn inmiddels verschenen, plus verhalen over de wereldkampioenen, David Bronstein en mijn persoonlijke favoriet: Evil-Doer, Half a Century with Viktor Korchnoi.

Zelf heb ik alleen in een simultaan tegen Sosonko gespeeld, dus dat telt niet. Wel heb ik Genna twee keer van dichtbij meegemaakt, telkens in een ontspannen sfeer. Een keer bij een lezing van Michael Tal voor de Nederlandse topjeugd, en een keer in de perskamer van Interpolis. Samen met Manuel Bosboom keek ik naar een stelling, en u begrijpt dat niet de meest normale zetten langskwamen. Nadat Sosonko enige tijd fronsend had staan toekijken, kon hij zich niet bedwingen en zei: “Nou, de NORMALE zet in deze stelling is dus…” (PvV)

Genna Sosonko

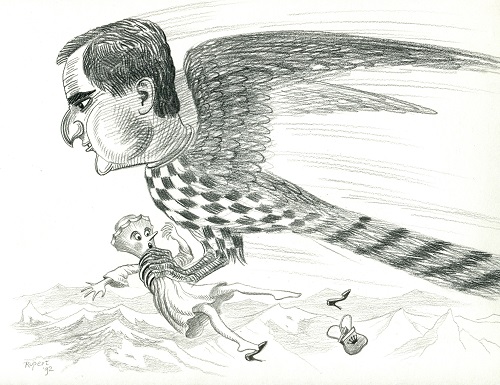

When Genna Sosonko boarded the plane from Leningrad to Vienna on 18 August 1972, it wasn’t only Russia that he left behind, but also a career as a trainer of the strongest of the strongest chess players. First he assisted Mikhail Tal, and later Viktor Kortchnoi – two completely different personalities, to be sure. Whereas, as Sosonko recalled, he’d had some trouble following Tal’s life rhythm, he and Kortchnoi kept addressing each other formally! Later, Genna told how the cooperation with Kortchnoi had been in a Dutch collection of chess interviews called De zuiverste liefde is die tussen een man en zijn paard: ‘In Russia, it’s common use to withdraw to a quiet house in the country. You train for four or five hours a day, and rest an awful lot. All that, in itself, is organized fantastically well.’ When asked by the interviewer, Max Pam, if the gloom didn’t creep up on him after a few days, Sosonko replied: ‘Well, what to say? Around here things are less professional, but that’s not so bad. As an individual, you have much more space here, and it’s also possible to become a strong chess player in the West.’

Sosonko himself is a good example. After his emigration, he first went to Israel, but soon after that he ended up in the Netherlands, where he knew the wife of Ton Sijbrands, the famous draughts player. In the Netherlands, he strung together a whole series of tournament victories, and he became Dutch Champion in 1973 – after a playoff with two rivals. His former professional work didn’t do any harm to his chess. His openings were especially dynamic: with black, the Dragon and the Ragozin – highly tactical openings, and certainly not every white player dared to take up the challenge, which of course suits the black player excellently. About his White repertoire Sosonko once said: ‘At move 3 on my scoresheet I can already write 3.g3 in advance.’ Except against the King’s Indian and the Grünfeld Indian, that is: against these openings he opted for classical set-ups.

In Russia, Genna had earned the title of National Master, but this title wasn’t valid outside Russia… he became an IM in 1974, and a Grandmaster in 1976. After that, a highly successful period started. He won Hoogovens twice (1977, 1981), conquered his second Dutch title (1978), and climbed up to the world top-20. As it turned out, this was his peak. In the World Championship cycles he qualified for two interzonal tournaments: Biel 1976 and Tunis 1985. The former came too early, and the latter too late, you might say, although in Tunis Genna only just missed the qualification spots. When playing for the Dutch Olympiad team, he lost only very rarely. I wonder which of his results Genna himself prefers: Haifa 1976 (gold medal on board 2 for himself, silver medal for the Netherlands) or Thessaloniki 1988 (playing captain, and the bronze medal). Quite a lot of countries didn’t take part in 1976, and the bronze medal in 1988 was a complete surprise.

Genna’s importance for Dutch chess can hardly be overrated. As a player, a trainer, a national coach and a chess writer, he helped many talented players on their way up. Therefore it was perfectly justified that he was granted the Max Euwe Ring in 2007, which he passed on in 2012 to another eminent national coach, Cor van Wijgerden. After Genna’s active career had ended, he set himself to writing about the past of Soviet players. Three volumes have appeared, plus stories about the World Champions, David Bronstein, and my personal favourite: Evil-Doer, Half a Century with Viktor Korchnoi.

I have only played one game against Sosonko – in a simul, so that doesn’t count. I did twice witness Genna from close by, in a relaxed atmosphere both times: once during a lecture by Mikhail Tal for Dutch top youth players, and another time in the pressroom of the Interpolis tournament. I was looking at a certain position with Manuel Bosboom, and as you will understand, it wasn’t the most normal moves that came on the board. After Sosonko had been watching, frowning, for some time, he could no longer constrain himself and said: ‘Well, the NORMAL move in this position is…’ (PvV)