Klokkijken is een nuttige eigenschap voor de schaker.

Nou zijn er natuurlijk ook spelers die daar een hobby van maken:

de tijdnoodspecialisten! In Nederland is Friso Nijboer de bekendste, maar wereldwijd verkeert hij in uitmuntend gezelschap. Uit het verleden schieten Samuel Reshevsky en Walter Browne me te binnen, en nu is Alexander Grischuk in elk geval het populairste lid van het genootschap. Reshevsky kwam in zijn autobiografie zelfs met een eenvoudige verklaring: “By playing slowly during the early phases of a game, I am able to grasp the basic requirements of each position. Then, despite being in time pressure, I have little difficulty in finding the best continuation.” Yeah, right…

Aan handleidingen om dit probleem aan te pakken natuurlijk geen gebrek. Dvoretsky pakte zijn pupillen stevig aan met een ‘anti-tijdnood’ training – juist tijdens een toernooi! Niet de kwaliteit van de partijen of het resultaat (slik!), maar het goede tijdgebruik is het doel: nooit minder dan zeg drie minuten per zet voor de rest van de bedenktijd. Er was nog geen increment natuurlijk… John Nunn duikt de psychologie in en noemt drie belangrijke redenen voor tijdnood: geen besluit kunnen nemen, te veel nadenken over minuscule verschillen en jezelf een excuus bezorgen. Axel Smith voerde een uitgebreide zelfanalyse uit en dwong zichzelf sneller te spelen, zoals hij beschrijft in ‘Pump up your rating’. Maar dat bleek merkwaardig genoeg niet zo eenvoudig…

In deze digitale tijden, waar je in alle rust je laatste seconden kan zien wegtikken, vergeet men allicht dat je voorheen echt klok moest kijken. Beter gezegd: kijken naar het vlaggetje. Nu waren er klokken die daar speciaal voor toegerust waren. Bij de Koopmanklok werden de laatste twee minuten handig uitvergroot en kon je tot op 10 seconden nauwkeurig schatten. De standaard Garde klok was ook nog wel redelijk in te schatten, maar ja, je had ook nog kleine BHB-klokjes, of de Russische Jantar. Plastic natuurlijk, maar wel goedkoop hoor…

Afijn, al snel was duidelijk dat Friso tot de categorie van ‘ongeneeslijken’ behoorde. Nou zal dat in zijn jeugd nog geen rol gespeeld hebben. Geboren en opgegroeid in Nijmegen en ‘dus’ spelend voor Strijdt Met Beleid en het Canisius-college van Pater Krekelberg. Jeugdkampioen tot en met dertien jaar in 1977, een gedeelde tweede plaats tot en met zestien jaar in 1980 en ten slotte jeugdkampioen tot en met twintig jaar in 1982. Daarna gaat het rustig verder en krijgt eerst de studie de voorrang. In 1988 wordt hij IM, en in 1993 GM.

Daarmee heeft Friso het niveau bereikt van vaste deelnemer aan het NK en maakt deel uit van het Nederlands team op Olympiades en Europese teamkampioenschappen. Hoogste ereplaats in het NK wordt de (gedeelde) tweede plek, het Open NK daarentegen wordt meerdere keren zijn prooi. Op de Olympiades weet hij alleen boven zichzelf uit te stijgen als hij in 2006 een vaste plaats krijgt. De Europese teamkampioenschappen zijn duidelijk meer Friso’s terrein: van de twintig gespeelde partijen verliest hij er maar één, en zijn individuele score is vaak veel beter dan de teamscore!

En Friso’s stijl? Compromisloos. Moordend met wit, en met zwart worden zwakkeren ook stevig aangepakt (Siciliaans of Hollands). Zijn spel met de witten was dermate gevreesd dat Paul van der Sterren hem als het ijkpunt beschouwde voor zijn Spaanse repertoire! Slechts tegen de allersterksten faalt Friso, maar vooral met zwart. Dat is geen schande, want er zijn maar enkele Nederlandse schakers die daaraan hebben kunnen ontsnappen.

Zelf heb ik maar een keer tegen Friso kunnen spelen. In de halve finales NK van 1984, toen ik op mijn top stond en Friso een aanstormend talent was. Zoals bekend mag zijn moet je opkomende sterke spelers verslaan als ze nog jong zijn! Na een rustige opening koos Friso voor de lange rokade met zwart in een Pirc. Nou was dat nog ruim voor Kasparov-Topalov (Wijk aan Zee, 1999), maar ook in dit geval was er een klein euvel en gingen twee pionnen & een kwaliteit in de doos. Heeft dat Friso geïnspireerd tot het schrijven van vier delen over Tactiek in de opening? Moet toch eens deel drie opslaan bij de Pirc… (PvV)

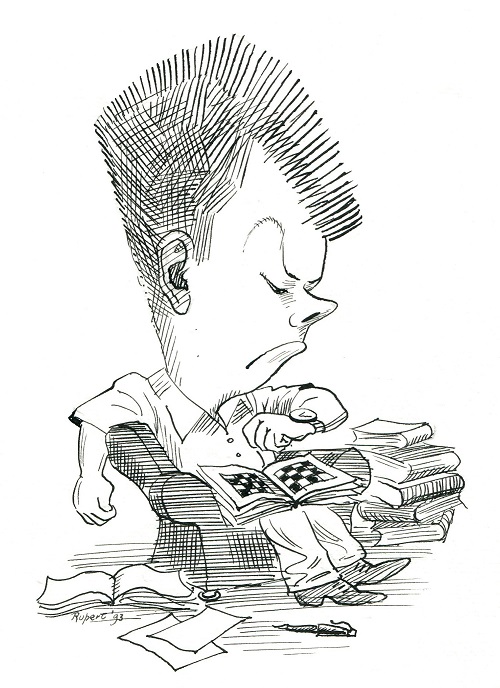

Friso Nijboer

Watching the clock is a useful occupation for every chess player. Of course, there are also players who turn this into a hobby – the time-trouble addicts! In the Netherlands, Friso Nijboer is the best known of them, but he is in excellent company worldwide. From the past, Samuel Reshevsky and Walter Browne come to my mind, and today, Alexander Grischuk is, at least, the most popular member of this society. In his autobiography, Reshevsky even came up with a simple explanation: ‘By playing slowly during the early phases of a game, I am able to grasp the basic requirements of each position. Then, despite being in time pressure, I have little difficulty in finding the best continuation.’ Yeah, right…

Of course there is no lack of instructions to tackle this problem. Dvoretsky dealt with his pupils in a resolute way, with an ‘anti-time-trouble training’ – during a tournament, not before or after! Neither the quality of the games, nor the result (gulp!) was the aim, but the right use of thinking time: never to have less than, say, three minutes per move for the remaining moves until the time control. Of course, there were no increments back then… John Nunn dives into the psychology of the game, and mentions three important causes of time-trouble: an inability to make decisions, too much thinking about minuscule differences, and making excuses for yourself. Axel Smith did an extensive self-analysis, and forced himself to play faster, as he described in his book Pump up your rating. However, strangely enough, this turned out not to be so easy…

In these digital times, in which you can quite calmly watch your last seconds ticking away, it is easy to forget that in the old days you really had to watch the clock, or rather: the flag. There were clocks that were specially equipped for this. On the Koopman clock, the final two minutes were conveniently magnified, which meant you could estimate accurately to up to ten seconds. On the standard Garde clock, you could also make a fairly accurate estimation, but then there were also those small BHB clocks, or the Russian Jantar clock. Plastic, of course, but very cheap, you know…

In any case, it quickly became clear that Friso belonged to the category of ‘incurables’. In his youth, this probably didn’t play much of a role yet. He was born and raised in Nijmegen, and ‘so’ played for Strijdt Met Beleid (‘Fight with Skill’) and Pater Krekelberg’s Canisius College. National U13 champion in 1977, shared second in the U16 championship in 1980 and, finally, junior U20 champion in 1982. After that he calmly carried on, giving priority to his study first. He became an IM in 1988, and a GM in 1993.

Friso had reached the level of regular Dutch Championship participants, and played on the Dutch team at Olympiads and European team championships. His best result in the Dutch Championship was (shared) second place, but the Dutch Open title was his prey several times. At the Olympiad, he didn’t manage to surpass himself until he got a permanent place in the team in 2006. Clearly, the European Team Championships were more Friso’s territory: of twenty games played there, he lost only one, and his individual score was often much better than the average team score!

Friso’s style? Uncompromising. A killer with white, and with black he also tends to deal sharply with weaker players (Sicilian or Dutch Defence). His play as White was so feared that Paul van der Sterren regarded Nijboer’s games as the yardstick for his Ruy Lopez repertoire! Friso only fails against the strongest of the strongest – mainly with black. That is no disgrace, since there are only very few Dutch players who have managed to avoid this.

I myself have only been able to play Friso once – in the Semifinals for the Dutch Championship in 1984, when I was at my playing peak, and Friso was an up-and-coming talent. As you may well know, you have to beat promising players while they are still young! After a quiet opening, Friso opted for queenside castling with black in the Pirc. Well, this was long before the game Kasparov-Topalov (Wijk aan Zee, 1999), but also in this case something went slightly wrong, and two pawns and an exchange went in the box. Was this the game that inspired Friso to write his four volumes on Tactics in the opening? Perhaps I should turn up Part 3 on the Pirc one of these days… (PvV)