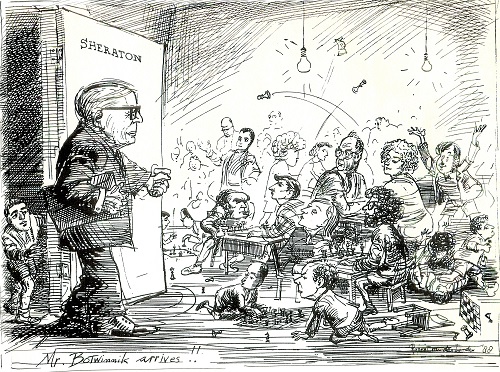

We schrijven het jaar 1988. In het luxueuze Sheraton-hotel in Brussel wordt het eerste wereldbekertoernooi gehouden. Een groot deel van de wereldtop is aanwezig. Sponsor is SWIFT en topman Bessel Kok heeft zijn uiterste best gedaan om de voormalige wereldkampioen Michail Botwinnik naar de opening te halen. Dat is gelukt. Hans Bouwmeester schreef daarover in Schakend Nederland: “De jonge schaakmeesters waren duidelijk erg onder de indruk, want ze kwamen de eerste ronde niet tot grote prestaties.”

Jonge schaakmeesters? Je kon deelnemers als Portisch, Kortsjnoi, Tal, Timman, Ljubojevic en Andersson toch bepaald geen jonkies noemen. Maar de boodschap is duidelijk, hier kwam een godheid binnen, een patriarch.

Nu had Botwinnik ook wel iets om op terug te kijken. Zesmaal kampioen van de Sovjet Unie, de eerste keer in 1931 toen hij net twintig was, de zesde keer in 1952. Maar vooral wereldkampioen schaken van 1948 tot 1963, met korte onderbrekingen toen eerst Smyslov en later Tal de titel voor een jaartje overnamen. Je zou hem vooral de kampioen van de tweekampen kunnen noemen, want afgezien van de vijfkamp uit 1948, toen hij de vacante wereldtitel veroverde, domineerde hij in tweekampen. Een gedegen, zeg maar minutieuze voorbereiding legde de basis voor zijn overwinningen. In toernooien was Botwinnik veel minder te zien, maar als hij wel meedeed won hij regelmatig. Zoals in het eerste grote naoorlogse toernooi: Groningen 1946, waar hij Euwe een half punt voor bleef.

Botwinnik werd door de buitenwacht nogal eens gezien als de ideale vertegenwoordiger van het Sovjetregime, als de gezagsgetrouwe schaker. Als dat al zo was dan wierp hij in zijn latere jaren de schroom om zijn mond open te doen van zich af. Toen Viktor Kortsjnoi in de jaren zeventig de Sovjet-Unie verliet weigerde hij een brief te ondertekenen waarin deze werd veroordeeld. In de Nieuwsbrief van het MEC (mei 2020) schreef Symon Algera: “De Sovjetschaakbond had met al zijn intriges voor een belangrijk deel zelf schuld aan de vlucht van Kortsjnoi, vond Botwinnik.”

Botwinnik lijkt altijd een zwak te hebben gehad voor Nederland. Hij speelde onder andere bij IBM en Hoogovens, was voorzitter van de Vereniging Nederland-USSR, en besloot zijn toernooicarrière in een vierkamp met Spasski, Larsen en Donner bij het Leidse LSG. Hij sprak ook een paar woorden Nederlands.

Misschien heeft de goede relatie die hij altijd met Euwe had ook een rol gespeeld. Afgezien van het feit dat ze beiden wereldkampioen waren, was er nog een overeenkomst. Beiden hadden ze een loopbaan buiten het schaken, beiden in de bètasector. Euwe was wiskundige en later hoogleraar informatica. Botwinnik was ingenieur in de elektrotechniek en kreeg in de jaren vijftig ook belangstelling voor computers en kunstmatige intelligentie. Omdat hij zich in zijn latere jaren ook met computerschaak ging bezighouden haalde hoogleraar informatica Jaap van den Herik hem regelmatig naar Nederland. Net als Van den Herik was Botwinnik er van overtuigd, al in 1970, dat de schaakcomputer ooit te sterk voor de mens zou worden. Hij overleed net te vroeg om mee te maken hoe Kasparov door Deep Blue werd verslagen. (MbdW)

In de MEC-Nieuwsbrief van juni 2020 schreef Symon Algera een uitvoerig artikel over de band tussen Botwinnik en Nederland

A visit by Botvinnik

It is the year 1988. In the luxurious Sheraton Hotel in Brussels, the first World Cup tournament is going to be held. A large contingent of world top players is present. SWIFT is the sponsor, and CEO Bessel Kok has done his utmost to get the former World Champion Mikhail Botwinnik to attend the opening of the event – and he has succeeded. Hans Bouwmeester wrote about it in Schakend Nederland: ‘Clearly the young chess masters were very impressed, as in the first round they were not capable of any great performances.’

Young chess masters? You couldn’t exactly call participants like Lajos Portisch, Viktor Kortchnoi, Mikhail Tal, Jan Timman, Lubomir Ljubojevic and Ulf Andersson youngsters, could you? But the message was clear: a deity was entering the building – a patriarch.

Now, Botvinnik was someone who did have a few things to look back on. Six-time champion of the Soviet Union, the first time in 1931 when he had just turned twenty, and the sixth time in 1952. But above all, he was World Champion from 1948 until 1963, with short intervals when first Vasily Smyslov and later Tal took over the title for a year. We might in fact call him the Match Champion, since, apart from the five-player event in 1948 where he conquered the vacant world title, he was especially dominant in matches. Thorough if not meticulous preparation formed the basis of his victories. In tournaments, Botvinnik was seen much less frequently, but when he took part, he regularly won them. In the first great post-war tournament, Groningen 1946, for example, where he edged out Max Euwe by half a point.

The outside world quite often viewed Botvinnik as the ideal representative of the Soviet regime – the law-abiding chess player. While it is questionable if that had ever been true, in his later years he shook off all his timidity and started speaking out. When Viktor Kortchnoi left the Sovjet Union in the 1970s, Botvinnik refused to sign an official letter in which he was condemned. In the MEC Newsletter of May 2020, Symon Algera wrote: ‘The Soviet Chess Federation itself, with all its intrigues, was largely to blame for Kortchnoi’s flight, Botvinnik thought.’

Botvinnik always seems to have had a soft spot for the Netherlands. He played, among others, at the IBM and Hoogovens tournaments, he was the chairman of the Netherlands-USSR Association, and concluded his tournament career by taking part in a four-player event with Boris Spassky, Bent Larsen and Hein Donner with LSG in Leiden. Also, he could speak a few words in Dutch.

Perhaps, the good relation he always had with Euwe played a role as well. Apart from the fact that they had both been World Champions, there was also another similarity. Both of them also had a career outside chess, both in science. Euwe was a mathematician and later a professor in computer science. Botvinnik was an electrical engineer who in the 1950s also developed an interest in computers and artificial intelligence. Because he also got involved in the development of computer chess in his later years, computer science professor Jaap van den Herik regularly got him to come to the Netherlands. Just like Van den Herik, Botvinnik was convinced, as early as 1970, that one day the chess computer would be too strong for human players. He passed away just before Kasparov got beaten by Deep Blue. (MbdW)

In the MEC Newsletter of June 2020, Symon Algera wrote an extensive article on Botvinnik’s ties with the Netherlands. (in Dutch)