“A picture is worth a thousand words”… dat geldt hier zeker voor de ervaringen met Advanced Chess.

Toen de computers eind jaren tachtig alsmaar sterker werden door verbeteringen in de software, werden matches georganiseerd tussen Mens en Machine om te kijken hoe nou eigenlijk de krachtsverhoudingen lagen. Naast individuele matches werd van 1986 tot en met 1997 een massaal toernooi georganiseerd door de Computer Schaak Vereniging Nederland, gefaciliteerd door Aegon in Den Haag. Ondanks de met de jaren steeds sterkere deelnemende spelers grepen de computers langzaam de macht. In 1994 vond de omslag plaats en sindsdien wonnen de computers. Een van de helden – aan menselijke kant – was John van der Wiel, die met een uitgekiende anti-computerstijl het Beest bijna altijd wist te temmen.

Schaken met behulp van – en niet tegen – de computer nam een grote vlucht in de voorbereiding van de dertiende wereldkampioen, Garry Kasparov. Nu is dat gemeengoed geworden voor alle topspelers, maar hij was de wegbereider. Na zijn pijnlijke verlies tegen IBM’s Deep Blue in 1997 had hij een ander idee: laat twee grootmeesters tegen elkaar spelen, terwijl ze computers kunnen raadplegen. “If you can’t beat them, join them…” De idee was natuurlijk dat het niveau zou stijgen doordat er minder (diepe tactische) fouten gemaakt zouden worden.

Wat kwam daarvan uit? In Leon (Spanje) werd van 1998 tot en met 2002 een Advanced Chess toernooi georganiseerd, met deelname van de wereldtop uit die jaren. Kasparov, Topalov, Anand en Kramnik gaven allen acte de présence. De toeschouwers zagen niet alleen het bord, maar ook schermen waar de spelers hun kandidaatzetten lieten testen door de computers.

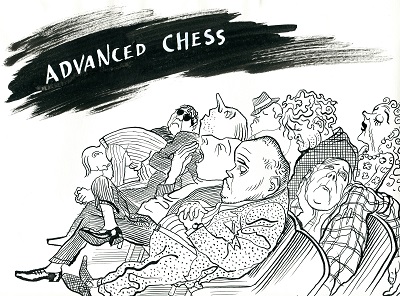

De resultaten waren teleurstellend. Kasparov legde zelf de vinger op een zere plek: als iemand gewonnen staat, is dat in feite het einde van de partij. Oftewel, weg met de wisselende kansen en schwindels. Terwijl ik de partijen naspeelde kreeg ik het sterke gevoel dat de spelers wat meer naar het echte bord hadden moeten kijken. Een ander verkooppraatje was dat het voor de kijkers interessant zou zijn om de kandidaatzetten van de grootmeesters te volgen: hum. Dan moet je natuurlijk wel het niveau hebben om die zetten te kunnen begrijpen! En zoals u ziet, de toeschouwers waren duidelijk niet geïnteresseerd…

Bij correspondentieschaak – raadplegen staat vrij – was vanzelfsprekend de computer een steeds belangrijker factor geworden. Waren er vroeger weinig grootmeesters die dat actief volgden, dat is inmiddels wel veranderd. Zeker wat geforceerde varianten betreft, neem bijvoorbeeld de Vergiftige pion variant in de Najdorf. Op een gegeven moment is alles in een loeischerpe variant gewoon aan de orde geweest en is de variant in feite dood. Ofwel wit staat beter (en dan vermijdt zwart deze) ofwel het staat gelijk (en dan vermijdt wit het op zijn beurt).

Natuurlijk is er nóg een vorm van ondersteuning door de computer mogelijk voor een schaakspeler. Maar ja, dat is verboden door de FIDE, de Wereldschaakbond, volgens artikel 11.3. 1 en verder:

“Tijdens het spelen is het spelers verboden gebruik te maken van enigerlei aantekening, informatiebron of advies of op een ander schaakbord welke partij dan ook te analyseren.”

Niet dat er helaas af en toe niet spelers zijn die het – hoe creatief ook – proberen… (PvV)

Advanced Chess

‘A picture is worth a thousand words’… this certainly applies to the experiences with Advanced Chess, illustrated here.

When in the late 1980s the computers became stronger all the time due to improvements in the software, matches between Man and Machine were organized, to see what the balance of forces was really like. Besides individual matches, an annual mass tournament was organized by the Computer Schaak Vereniging Nederland from 1986-1997, facilitated by Aegon in The Hague. Even though the participants became stronger with the years, the computers slowly seized power. The reversal took place in 1994, and since then the computers always won. One of the heroes – on the human side – was John van der Wiel, who almost always managed to tame the Beast with his cunning anti-computer style.

Chess with the help of – instead of against – the computer really took off in the way the thirteenth World Champion, Garry Kasparov, prepared his games. Today this has become widely accepted with all the top players, but Kasparov was the trailblazer. After his painful defeat at the hands of IBM’s Deep Blue in 1997 he had a different idea: let two grandmasters play each other, allowing them to consult computers: ‘If you can’t beat them, join them…’ The idea was, of course, that the level of the play would rise because less (deep tactical) mistakes would be made.

Was it a success? In Leon (Spain), an Advanced Chess tournament was organized from 1998-2002, where the world top players of the time took part. Kasparov, Topalov, Anand and Kramnik all made an appearance. The spectators saw not only the board, but also screens on which the players let the computers test their candidate moves.

The results were disappointing. Kasparov himself put the finger on the sore spot: if one side is winning, then in fact that’s already the end of the game. In other words – no more changes of fortune or swindles. Playing through the games I got a strong feeling that the players should have looked at the actual board a little more. Another sales pitch was that it would be interesting for the audience to follow the candidate moves of the grandmasters – hm. Then of course you will need to have the right level to understand those moves! And, as you see above, the spectators were clearly not interested…

Evidently, with correspondence chess – where consultation is allowed – the computer became an ever more important factor. While in former days there were few grandmasters who followed the developments in this branch of chess, this has certainly changed today – especially in the case of forced variations, such as in the Najdorf Poisoned Pawn Variation. In such razor-sharp variations, at a certain point everything has been discussed, and then the variation is in fact dead. Either White is better (in which case Black will avoid this line) or the position is equal (and then White in turn will avoid it).

Of course, there is still another form of computer support possible for a chess player. But that is prohibited by FIDE, Article 11.3.1 and further:

‘During play the players are forbidden to use any notes, sources of information or advice, or analyse any game on another chessboard.’

Not that, alas, there aren’t any players every now and then who do try this – however creatively… (PvV)