De meeste schakers bereiken hun top als ze in de twintig of dertig zijn. Je hoogtepunt bereiken als je 44 bent, het is het jaar 2012, mag je dus best bijzonder noemen. Want zo kan je een match om de wereldtitel toch wel noemen. Zeker als die tegen een titelverdediger als Anand in 6-6 eindigt, je een voorsprong uit handen hebt gegeven en je pas in de aansluitende rapidpartijen met een 2½-1½ nederlaag je kans op de hoogste titel verloren ziet gaan.

Toch kunnen we Boris Gelfand niet een laatbloeier noemen want al in 1991, hij was toen 23, plaatste hij zich voor de kandidatenmatches. Na winst tegen Nikolic bleek Nigel Short een maatje te groot. Vier jaar later, in 1995, kwam hij verder en bereikte hij de finale van de kandidatenmatches. Dit keer sneed Anatoli Karpov hem de pas af. Daarna duurde het een paar jaar voor hij in de strijd om de wereldtitel weer van zich deed spreken. In 2007 werd in Mexico voor het eerst sinds 1948 in toernooivorm om de wereldtitel gespeeld. Gelfand die in de tussenliggende jaren een absolute topspeler was gebleven plaatste zich voor dit toernooi en eindigde als oudste speler samen met Kramnik op de tweede plaats, een punt achter winnaar Anand.

Boris Gelfand werd op 24 juni 1968 geboren in Minsk, de hoofdstad van Wit-Rusland dat toen een onderdeel van de Sovjet-Unie vormde. Het was al vroeg duidelijk dat hij schaaktalent had, want al op zijn zesde kreeg hij een trainer. Het duurde daarna nog wel even tot de echte doorbraak kwam, maar op zijn zestiende won hij dan toch het kampioenschap van Wit-Rusland, bij de senioren, en een jaar later werd hij jeugdkampioen van de Sovjet-Unie. Dat hij in 1988 geen wereldkampioen bij de jeugd werd kwam doordat het Franse talent Joël Lautier net even sterker bleek.

Hij had bij die ontwikkeling de onvoorwaardelijke steun van zijn ouders, vooral zijn vader die zijn grootste fan werd. Vader Gelfand stelde maar liefst zestig albums samen met alles over de schaakcarrière van zijn zoon. Over de match tegen Anand werd in Israël een film gemaakt die als eerbetoon aan de verzamelende vader de titel Het 61ste album kreeg. Vader Gelfand was toen overleden. De film werd op het filmfestival van Sao Paulo bekroond met de onderscheiding ‘Beste film’.

In 1989 werd Gelfand grootmeester en in de daaropvolgende twintig jaar won hij heel wat toptoernooien. In Wijk aan Zee was hij tien keer te bewonderen. Zijn beste resultaat, een met Salov gedeelde eerste plaats, noteerde hij bij zijn eerste optreden in 1992.

Zoals bekend viel de Sovjet-Unie in de jaren negentig van de twintigste eeuw uiteen. Dat had voor Gelfand het gevolg dat hij op de Olympiade eerst voor de Sovjet-Unie uitkwam en daarna voor Wit-Rusland. Toen hij in 1998 naar Israël verhuisde kwam daar een derde land bij. Zijn beste teamresultaat, een eerste plaats, behaalde hij zoals te verwachten was met de Sovjets, maar ook met Israël ging het lang niet slecht. In 2008 en 2010 werd dat land met Gelfand aan het eerste bord respectievelijk tweede en derde.

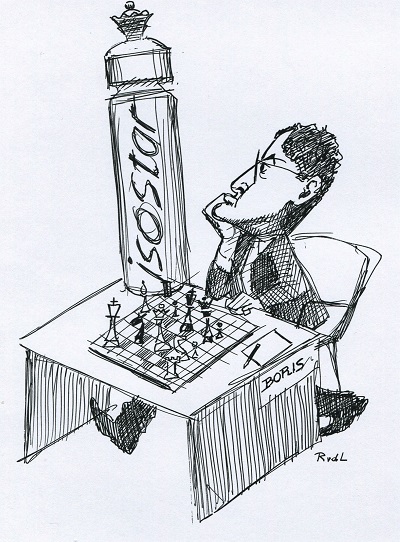

Wie Gelfand wel eens heeft zien spelen zal het zijn opgevallen dat hij in tegenstelling tot veel van zijn collega’s niet doorlopend diep over het bord gebogen zit, maar nogal eens naar het plafond staart of met fikse stappen door de toernooizaal ijsbeert. Is dat concentratieverlies? Integendeel, zei hij in een interview. “Door de spanning kan je niet stilzitten, daarom loop je. Toch blijf je de hele tijd diep nadenken. Je hoofd werkt even intensief als wanneer je aan de tafel zit.” Zijn resultaten bewijzen het gelijk van zijn redenering. (MbdW)

Boris Gelfand missed the world title by a hair

Most chess players reach the height of their powers when they are in their twenties or thirties. To reach your peak at 44 – this was in the year 2012 – can be called something quite special. And special is what we may call a match for the world title, certainly if you end it on 6-6 against a title defender like Viswanathan Anand, after having let the lead slip out of your hands, and your chances at the highest title finally disappear in an ensuing 2½-1½ defeat in the rapid playoff.

Still we cannot call Boris Gelfand a late-bloomer, since he already qualified for the Candidates Matches in 1991, when he was 23. After he had defeated Predrag Nikolic, Nigel Short proved to be out of his league. Four years later, in 1995, Gelfand got further in the cycle, reaching the final of the Candidates Matches. This time it was Anatoly Karpov who blocked his path. It took a few years before he stepped back into the spotlights in the struggle for the world title. In 2007, in Mexico, the World Championship was decided in a tournament for the first time since 1948. Gelfand, who had proved to be an absolute top player in the intervening years, qualified for the tournament. The oldest player in the field, Boris shared second place with Vladimir Kramnik, one point behind the winner, Viswanathan Anand.

Boris Gelfand was born on 24 June 1968 in Minsk, the capitol of Belarus which was then part of the Soviet Union. Soon it became clear that he had a talent for chess – he already had a trainer when he was six years old. It took a while before the real breakthrough came, but at sixteen he did win the Belarus Senior Championship, and one year later he became Junior Champion of the Soviet Union. In 1988 he failed to win the Junior World Championship only because the French talent Joël Lautier proved to be just a little stronger.

Throughout his entire development he had the unconditional support of his parents, especially his father, who was his greatest fan. Father Gelfand compiled no less than sixty albums filled with all the available material on his son’s chess career. A film was made in Israel on the match against Anand, which was titled The 61st album as an homage to his collector-father, who had passed away by this time. It was honoured with the ‘Best film’ award at the Sao Paulo film festival.

Gelfand became a grandmaster in 1989, and he won quite a few top tournaments in the next twenty years. His fans could admire him ten times in Wijk aan Zee. His best result there was first place shared with Valeri Salov, at his first outing in 1992.

As is well-known, the Soviet Union fell apart in the 1990s. As a result, Gelfand, who had always played for the Soviet Union at Olympiads, was now lined up in the Belarus team. After his move to Israel in 1998 a third country was added to the list. Not unexpectedly, he achieved his best team result – first place – with the Soviets, but he didn’t do at all badly with Israel either. In 2008 and 2010, that country, with Gelfand on first board, came second and third respectively.

If you have seen Gelfand play, it may have struck you that, contrary to his colleagues, he is not sitting at the board bent deeply over the pieces all the time, but quite often sits staring at the ceiling or paces up and down the playing venue with firm steps. Does this signify loss of concentration? On the contrary, he said once in an interview: ‘Due to the tension you can’t sit still, that’s why you walk around. But all this time you are still thinking deeply. Your mind is working just as intensively as when you’re sitting at the table.’ His results prove him right. (MbdW)

Boris Gelfand missed the world title by a hair

Most chess players reach the height of their powers when they are in their twenties or thirties. To reach your peak at 44 – this was in the year 2012 – can be called something quite special. And special is what we may call a match for the world title, certainly if you end it on 6-6 against a title defender like Viswanathan Anand, after having let the lead slip out of your hands, and your chances at the highest title finally disappear in an ensuing 2½-1½ defeat in the rapid playoff.

Still we cannot call Boris Gelfand a late-bloomer, since he already qualified for the Candidates Matches in 1991, when he was 23. After he had defeated Predrag Nikolic, Nigel Short proved to be out of his league. Four years later, in 1995, Gelfand got further in the cycle, reaching the final of the Candidates Matches. This time it was Anatoly Karpov who blocked his path. It took a few years before he stepped back into the spotlights in the struggle for the world title. In 2007, in Mexico, the World Championship was decided in a tournament for the first time since 1948. Gelfand, who had proved to be an absolute top player in the intervening years, qualified for the tournament. The oldest player in the field, Boris shared second place with Vladimir Kramnik, one point behind the winner, Viswanathan Anand.

Boris Gelfand was born on 24 June 1968 in Minsk, the capitol of Belarus which was then part of the Soviet Union. Soon it became clear that he had a talent for chess – he already had a trainer when he was six years old. It took a while before the real breakthrough came, but at sixteen he did win the Belarus Senior Championship, and one year later he became Junior Champion of the Soviet Union. In 1988 he failed to win the Junior World Championship only because the French talent Joël Lautier proved to be just a little stronger.

Throughout his entire development he had the unconditional support of his parents, especially his father, who was his greatest fan. Father Gelfand compiled no less than sixty albums filled with all the available material on his son’s chess career. A film was made in Israel on the match against Anand, which was titled The 61st album as an homage to his collector-father, who had passed away by this time. It was honoured with the ‘Best film’ award at the Sao Paulo film festival.

Gelfand became a grandmaster in 1989, and he won quite a few top tournaments in the next twenty years. His fans could admire him ten times in Wijk aan Zee. His best result there was first place shared with Valeri Salov, at his first outing in 1992.

As is well-known, the Soviet Union fell apart in the 1990s. As a result, Gelfand, who had always played for the Soviet Union at Olympiads, was now lined up in the Belarus team. After his move to Israel in 1998 a third country was added to the list. Not unexpectedly, he achieved his best team result – first place – with the Soviets, but he didn’t do at all badly with Israel either. In 2008 and 2010, that country, with Gelfand on first board, came second and third respectively.

If you have seen Gelfand play, it may have struck you that, contrary to his colleagues, he is not sitting at the board bent deeply over the pieces all the time, but quite often sits staring at the ceiling or paces up and down the playing venue with firm steps. Does this signify loss of concentration? On the contrary, he said once in an interview: ‘Due to the tension you can’t sit still, that’s why you walk around. But all this time you are still thinking deeply. Your mind is working just as intensively as when you’re sitting at the table.’ His results prove him right. (MbdW)