Een kangoeroe die schaakspeelt in een smoking? Wat moet ik daar nou van maken, Rupert? Wel met wit spelend overigens en dat is een beetje in strijd met de oorsprong van het woord. Het komt namelijk van ‘gangurru’ en dat betekent zwarte kangoeroe…

Goed, Barejev dus. Hoe vaak zal het voorkomen dat je meest felle herinnering aan een speler de zet van een tegenstander is? Bij Barejev is dat zo voor mij. Niet zijn fantastische boek, From London to Elista, dat hij – samen met Ilja Levitow – schreef over de eerste drie WK matches van Kramnik. En ook niet zijn levenslange trouw aan de Franse verdediging. Nee, dat is 20…Ld6-c7! uit de partij Barejev-Van der Sterren, Biel 1993. Wie enigszins met mij wil meevoelen, grijpe naar Zwart op wit, Verslag van een schakersleven en sla dan pagina 345 op. Lees en huiver…

Barejev kreeg zijn schaakopleiding aan de Smyslov-school in (toen nog) de Sovjet-Unie. Niet dat hij daarbij Smyslov van dichtbij zag: hij komt zelf op een paar keer tijdens de vijf jaar dat hij de school bezocht. De andere coaches (onder andere Dvoretsky en Razuvajev) namen het echte werk voor hun rekening. Hijzelf is heel positief over de school – de Sovjet-Unie was een land van grote afstanden en er zijn maar weinig goede coaches! De scholing levert snel resultaat op: in 1982 wint hij het WK onder zestien jaar in Guayaquil. Maar daarna duurt het relatief lang eer hij grootmeester wordt: pas in 1989.

Net zoals Adams bereikt Barejev in de jaren negentig en het begin van de twintigste eeuw de top van zijn kunnen. Twee keer vierde van de wereld op rating, maar echt succes op een WK zit er niet in. Hij haalt maar één keer de laatste vier: in het kandidatentoernooi Dortmund 2002. Dat is merkwaardig voor zo’n sterke speler. Ik denk dat Barejev meer een toernooispeler dan een matchspeler is: in een toernooi is een nederlaag geen ramp, in de korte World Cup matches wel. Impliciet geeft hij dat ook toe in zijn verkapte autobiografie Say No to Chess Principles!: “In all I played no fewer than five such knockout events, and was able to bounceback only a handful of times”…

Barejev was naast een topspeler ook een succesvol secondant in de matches van Kramnik tegen Kasparov en Leko. Van de witte kant dan, en met uitzondering van de Grünfeld! Meestal samen met Lautier, waarbij hij het – merkwaardig genoeg – vooral prettig vond om in Parijs te analyseren. Dat Barejev zijn hele leven lang praktisch alleen maar 1.d4 heeft geopend is daar natuurlijk niet vreemd aan. Zijn zwaarste opgave als secondant zal ongetwijfeld de laatste partij tegen Leko geweest zijn. De opdracht van Kramnik was eenvoudig: weerleg de Caro-Kann met behulp van 3.e5… Nou speelde Barejev met zwart vooral Frans, maar ook Caro-Kann: hij zal dus geweten hebben waar de pijnpunten waren. Afijn, de rest is geschiedenis: Kramnik won en behield zijn titel!

De manier waarop Barejev partijen becommentarieert is zeer typerend. Hij spaart zichzelf bepaald niet, maar doet dat met zoveel humor dat de conclusies je bijblijven. Dat is absoluut terug te vinden in zijn autobiografische boek. Met thema’s als ‘A Queen behind enemy lines’ en ‘Killer delayed castling’ verkent hij de buitengebieden van het schaken, waar de principes nog niet ontdekt zijn. Wellicht dat hij hoopt dat hij evenals de spelers die hij in zijn voorwoord noemt – Aljechin, Capablanca, Spassky, Petrosjan, Botwinnik en … Anand – later tot de klassieken mag toetreden! (PvV)

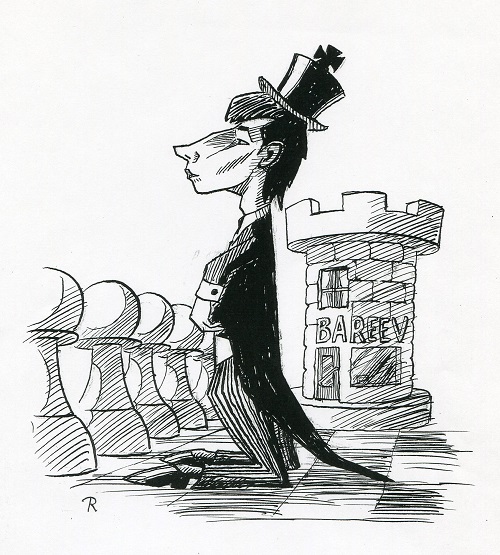

Evgeny Bareev

A kangaroo playing chess in smoking? What am I supposed to make of that, Rupert? It’s playing with white, by the way, which is slightly contrary to the origin of the word ‘kangaroo’ – since ‘gangurru’ in fact means ‘black kangaroo…’ Alright then, Bareev. How often does it happen that your strongest memory of a player is a move made by one of his opponents? For me, that is the case with Bareev. Not his fantastic book From London to Elista about Vladimir Kramnik’s first three World Championship matches, which he wrote together with Ilya Levitov. Also, not his life-long loyalty to the French Defence. No, it is the move 20…Bd6-c7! from the game Bareev-Van der Sterren, Biel 1993. If you want to see what I mean, then please take hold of Van der Sterren’s book Zwart op wit, Verslag van een schakersleven (= Black on White, the account of a chess player’s life’) and turn to page 345. Read it and weep…

Bareev received his chess education at the Smyslov school in the former Soviet Union. Not that he was able to watch Smyslov from close by: he recalls seeing him only a few times during the five years he attended the school. The other coaches (among others, Dvoretsky and Razuvaev) were doing the real work. Bareev is very positive about the school – the Soviet Union was a land of long distances, and there are only few good coaches! His schooling quickly led to good results: in 1982 he won the World U16 Championship in Guayaquil. But after that it took him a relatively long time to become a grandmaster – not until 1989.

Just like Michael Adams, Bareev reached his peak in the 1990s and early 2000s. Twice he stood fourth in the world on rating, but he couldn’t achieve any real successes in the World Championship cycles. Only once did he make it to the final four: in the Candidates Tournament in Dortmund 2002. That is curious for such a strong player. I think that Bareev is more a tournament player than a match player: during a tournament, one defeat is not a disaster, but in the short World Cup matches, it is. He admitted this implicitly in his semi-autobiography titled Say No to Chess Principles!: ‘In all I played no fewer than five such knockout events, and was able to bounce back only a handful of times’…

Besides a top player, Bareev was also a successful second to Kramnik for the latter’s matches against Kasparov and Leko – from the white side, that is, and with the exception of the Grünfeld! Mostly he worked together with Joel Lautier, and curiously enough he found it especially pleasant to analyse in Paris. The fact that Kramnik hired him as a second was not unrelated to the fact that during his entire career practically Bareev’s only opening move has been 1.d4. His toughest task was doubtlessly before the final game in the match with Leko. Kramnik’s assignment was simple: refute the Caro-Kann by means of 3.e5… In fact, Bareev mainly played the French with black, but also the Caro-Kann, so he must have known where the painful areas were. Anyway, the rest is history: Kramnik won, and kept his title!

The way in which Bareev gives comments on games is quite typical. He doesn’t spare himself at all, but does it with so much humour that the conclusions get stuck in your mind. This absolutely applies to his autobiographical book. With themes like ‘A Queen behind enemy lines’ and ‘Killer delayed castling’ he explores the outlying areas of chess, where no principles have been discovered yet. Perhaps he hopes that, just like the players he mentions in his foreword – Alekhine, Capablanca, Spassky, Petrosian, Botwinnik and… Anand – he will later be admitted to the ranks of the classics! (PvV)