Tegenwoordig is het in de perskamer van een schaaktoernooi vaak een saaie boel. Als er al mensen zijn dan zitten ze de meeste tijd naar het scherm te staren. Af en toe wordt er een woord gewisseld met een andere aanwezige.

Dat was vroeger, tot begin eenentwintigste eeuw, heel anders. Toen was de perskamer, samen met de speelzaal natuurlijk, het hart van een toernooi. Monitoren waren er niet, internet was nog nauwelijks doorgedrongen. In de speelzaal stonden achter de spelers grote demonstratieborden waarop bordenjongens de partijen bijhielden, de een wat beter en nauwkeuriger dan de ander. ‘Loopjongens’ zorgden ervoor dat de zetten van de speelzaal naar de perskamer werden gebracht en van daaruit kon de verspreiding naar de wijde wereld beginnen.

Als een journalist zich ter plaatse wilde informeren, bijvoorbeeld om te kijken hoe het met de gebruikte tijd stond of hoe nerveus een speler was, dan liep hij doodleuk de speelzaal in en stelde zich in gepaste stilte naast het bord op. Alsof een voetbalverslaggever naast de doelpaal gaat staan om te zien of de bal werkelijk de doellijn heeft gepasseerd.

Na afloop van een partij haastten de spelers zich naar de perskamer om daar, omringd door de pers en collega’s nog eens te kijken waar het nu mis was gegaan. Dat de journalisten zich soms vrolijk met de analyse bemoeiden, niemand die zich daar aan stoorde. Zo vreemd was dat ook niet, want menig schaakjournalist was in vroegere dagen zelf een actief toernooispeler geweest en had de meester- of grootmeestertitel op zak.

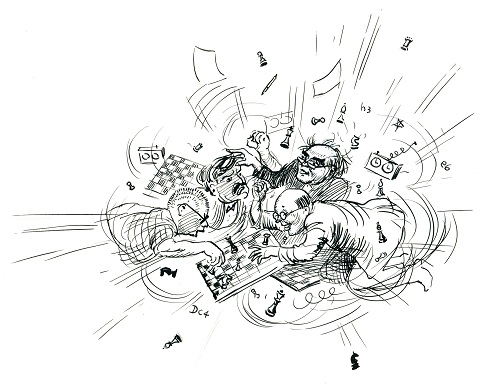

Vlogen de heren journalisten, dames waren er zelden bij, elkaar af en toe in de haren zoals Rupert suggereert? Welnee. Er werd gediscussieerd, gefilosofeerd, de wereld doorgenomen en soms ook gevluggerd als het allemaal wat saai was in de speelzaal, of als de periode van het diepe denken was aangebroken en het even kon duren voor er weer een zet naar de perskamer doorsijpelde. Alleen bij dat snelschaken vlogen de vonken er vanaf. Bovenal heerste er een opgewekte stemming. Elkaar vliegen afvangen, zoals in de grote journalistenwereld, was er nauwelijks bij. Daarvoor was de liefde voor het schaken te groot.

Vanaf de jaren negentig verdween dit folkloristisch aandoende wereldje geleidelijk. Eerst werden de journalisten uit de speelruimte verbannen, daarna namen monitoren en internet de verspreiding van de zetten over. Voor de pers bleef de duiding over en die kon, zo werd langzaamaan duidelijk, vaak net zo goed vanuit huis worden gedaan. Met de journalisten verdween geleidelijk ook hun aanhang en entourage. De perskamer veranderde van sociaal middelpunt in een technisch centrum. (MbdW)

Journalists having a romp

Pressrooms at chess tournaments are often dull places these days. If there are any people at all, they will be sitting and staring at screens most of the time. Now and then a few words are exchanged with another visitor.

In the old days, until the early 21st century, it was very different. The pressroom, together with the playing hall, of course, used to be the heart of any tournament. There were no monitors, the Internet had hardly penetrated into chess life. Behind the players in the playing hall, there would be large demonstration boards on which ‘board boys’ kept track of the games, one a little better and more accurate than the other. ‘Errand boys’ conveyed the moves from the playing hall to the pressroom, and from there their spreading over the wide world could begin.

If a journalist on the spot wanted to know something, for instance how the time situation was, or how nervous a certain player was, then he could simply walk into the playing hall and stand right next to the board, while remaining suitably quiet. As if a football reporter is standing beside the goal post to see whether the ball really passes the line.

After a game ended, the players would hurry to the pressroom, to sit down there and find out what had gone wrong, surrounded by the press and their colleagues. Sometimes the journalists would cheerfully interfere in the analysis, but there was no-one who minded that. Which wasn’t so strange actually, since many a chess journalist had been an active tournament player himself in former days, and carried the International Master or Grandmaster title.

Did the gentlemen journalists – there were hardly any ladies among them – fly at each other from time to time, as Rupert suggests in his cartoon? Not at all. They would debate, philosophize, talk about the situation in the world, and sometimes start playing blitz if there wasn’t much going on in the playing hall, or when the time of deep thinking had come and it could take some time before a new move would seep through to the pressroom. The sparks flew about only when they were playing blitz. Above all, there was a cheerful atmosphere. People hardly ever tried to score off each other, as does happen in the ‘big world’ of journalism. Everyone’s love of chess was too great for that.

Starting in the 1990s, this rather folkloristic scene gradually disappeared. First, the journalists were banned from the playing space, then the distribution of the moves was taken over by monitors and the Internet. It remained for the press to provide interpretation, and, as slowly became clear, that was something that could be done just as well from home. With the journalists, their followers and their entourage also gradually disappeared. The pressroom changed from a social hotspot into a technical centre. (MbdW)