Op het eerste gezicht lijkt hij een van die meesters te zijn die een tijdlang tot de subtop van het nationale schaken behoorde. Een laatbloeier bovendien, want de FIDE kende hem pas in 1986 de titel Internationaal Meester toe toen hij al 38 was. Om het meteen even over dat late bloeien te hebben, dat valt wel mee. Op zijn negentiende maakte hij deel uit van het team van Philidor Leeuwarden dat de enige landstitel in de clubcompetitie naar Friesland bracht. En vier jaar later speelde hij zijn eerste Nederlands kampioenschap. Hij werd negende.

Uiteindelijk zou hij zeven keer aan dat kampioenschap meedoen, verspreid over de periode 1971 tot 1987. Dat op en af meespelen geeft al aan dat hij op dat moment weliswaar tot de zeg toptwintig van Nederland behoorde, maar geen vaste waarde voor de top tien was.

Zijn beste NK was ongetwijfeld het toernooi van 1985. Niet alleen omdat hij vierde werd, maar vooral vanwege het diepzinnige, rechtlijnige spel dat hij liet zien. Zo versloeg hij Hans Ree met een dame-offer op lange termijn, dat nog altijd futuristisch aandoet. Het bondsblad Schakend Nederland schreef over hem: “Van Paul Boersma is al lang bekend dat hij een fijnzinnig stilist is, maar de wijze waarop hij dat in dit toernooi bevestigde zal menigeen hebben verbaasd.” Zelf besloot hij zijn analyse van de partij tegen Ree met de woorden: “Wat mooi dat dit allemaal kan in het schaakspel!”

Misschien komen we met deze woorden wel bij de kern van de schaker Paul Boersma, het zoeken naar de zuiverheid in het schaken. Had dat te maken met zijn filosofische inslag? De wil om door te dringen tot de kern? De behoefte aan helderheid? Het lijkt erop, want in het bondsblad schreef hij een enkele keer over de ethische kant van het schaken en hield hij een pleidooi voor de gentleman-schaker. Overigens had dat zoeken naar de waarheid van het schaken, om met de voeten op aarde terug te keren, zijn keerzijde. Het kostte namelijk veel tijd. Gruwelijke tijdnood was daarom een demon die Paul Boersma met grote hardnekkigheid moest bestrijden.

Paul Boersma was jarenlang een trouw en actief competitiespeler. In 2011, toen hij al gestopt was als schaker, had hij voor achtereenvolgens Philidor Leeuwarden, Utrecht en HSG 310 partijen in de hoogste klasse van de competitie gespeeld. Daarmee stond hij eerste op de ranglijst. Pas veel later wist Friso Nijboer (313 partijen) hem te passeren.

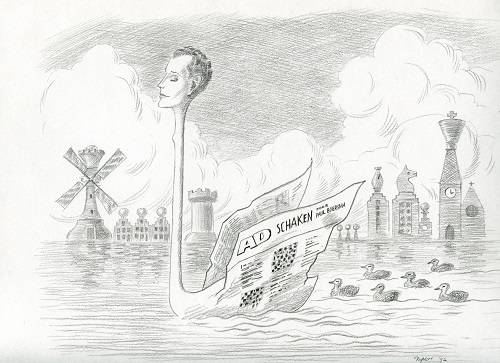

Omdat je van schaak spelen alleen niet kunt leven zocht en vond Paul Boersma neveninkomsten in het schrijven over schaken. Hij schreef drie boeken over het Siciliaans, schreef onder andere voor het bondsblad en werd landelijk vooral bekend door zijn wekelijkse rubriek in het Algemeen Dagblad. Hij volgde in 1988 Berry Withuis op, die hem bij de lezers introduceerde met bovengenoemde partij tegen Ree. Om te laten zien: met hem is de opvolging in goede handen.

Boersma gebruikte zijn laatste rubriek in augustus 1999 om een blik in de toekomst te werpen. Echt optimistisch is hij niet en heel kenmerkend wijst hij op de kern van het schaken. “De pracht van het schaken wordt pas doorgrond na studie en is niet makkelijk over te brengen op mensen, die slechts zijdelings zijn geïnteresseerd.” Maar toch ook als positieve slotzin: “Het schaakspel zal blijven boeien en niet alleen een onderwerp van cultuurhistorici zijn.”

Intussen is Paul Boersma al weer lang geleden gestopt met schaken. De laatste partijen die de FIDE voor de rating verwerkte stammen uit 2006. Stilzitten doet hij intussen niet. Op zijn website vertelt hij dat hij in 1981 in aanraking kwam met Vipassana meditatie, “Voor mij een openbaring”. Tegenwoordig geeft hij Vipassana-cursussen, is hij gastdocent en leraar op aanpalende opleidingen en heeft hij boeken vertaald over de innerlijke eenheid der religies, Soefisme en Boeddhisme. Doordringen tot de kern, het lijkt de leidraad van zijn leven. (MbdW)

Paul Boersma wanted to get to the very core of chess

At first sight, he seems to be one of those masters who belonged to the sub-top of Dutch chess for a considerable amount of time. A late-developer, too. FIDE awarded him the International Master title only in 1986, when he was already 38. This late development, by the way – it wasn’t that bad. At 19 he was a member of the Philidor Leeuwarden team that took the only national title in the club competition that ever went to the proud province of Frisia. And four years later he played his first Dutch Championship, coming 9th.

In total, he took part in this Championship seven times, spread over the period of 1971 to 1987. The fact that now he participated, and now he didn’t, already indicates that he belonged more or less to the Dutch top-20 in those years, but that he was no fixed value in the top-10.

His best Dutch Championship was doubtlessly the 1985 tournament – not only because he came fourth, but especially because of the profound, consistent play he showed. He defeated Hans Ree, for example, with a long-term queen sacrifice that still looks futuristic today. Schakend Nederland, the federation’s magazine, wrote about him: ‘We’ve known for a long time that Boersma is a subtle stylist, but the way he confirmed this in this tournament must have surprised many.’ Boersma himself concluded his analysis of the game versus Ree with the words, ‘How beautiful that all this is possible in chess!’

Perhaps these words touch the core of Paul Boersma as a chess player: a searcher for purity in chess. Did it have to do with his philosophical slant? His desire to get down to the very core? His craving for clarity? It looks like it, since on one occasion he wrote about the ethical side to chess in the federation’s magazine, and held a plea for the gentleman-chess player. But to get with our feet back on the ground – this continuous quest for the truth in chess had its downside: it took a lot of time. For that reason, horrible time-trouble was a demon Paul Boersma had to combat with great tenacity.

Paul Boersma was a loyal and active competition player for years. In 2011, when he had already quit as a chess player, he had played 310 games in the highest league of the Dutch competition, for Philidor Leeuwarden, Utrecht and HSG respectively. With this, he was first on the list, and only much later Friso Nijboer managed to overtake him with 313 games.

Because you can’t make a living on playing chess alone, Paul Boersma sought and found additional income by writing on chess. He wrote three books on the Sicilian, made articles for, among others, the federation’s magazine, and became nationally known especially by his weekly column in the newspaper Algemeen Dagblad, succeeding Berry Withuis in 1988, who introduced Paul to the readers with the above-mentioned game against Ree. Just to show that his succession was in good hands with Boersma.

Boersma used his final column in August 1999 for a glance into the future. He wasn’t exactly optimistic, and, very characteristically, he pointed at the core of chess: ‘The splendour of chess can only be fathomed after study, and it is not easy to convey it to people who are only indirectly interested.’ But he did conclude on a positive note: ‘The game of chess will continue to captivate, and will not only be a subject for cultural historians.’

It’s been quite a long time since Paul Boersma quit chess. His last games processed by FIDE for the Elo ratings date from as long ago as 2006. In the meantime he hasn’t sit still. On his website, he reports that he came into touch with Vipassana meditation in 1981; ‘For me this was a revelation.’ Nowadays he gives Vipassana courses, works as a visiting lecturer and teacher at adjacent trainings, and translates books on the inner unity of the religions, Sufism and Buddhism. Getting down to the core – it seems to be the guiding principle of his life. (MbdW)