by Paul van der Sterren

In the years after our simultaneous game, I would occasionally encounter the great man – in fact, he would be present at the opening or closing ceremony of almost every important tournament that I played – but it wasn’t until the final year of my youth that I caught a glimpse of the power that resided within him, the silent force with which he influenced lives.

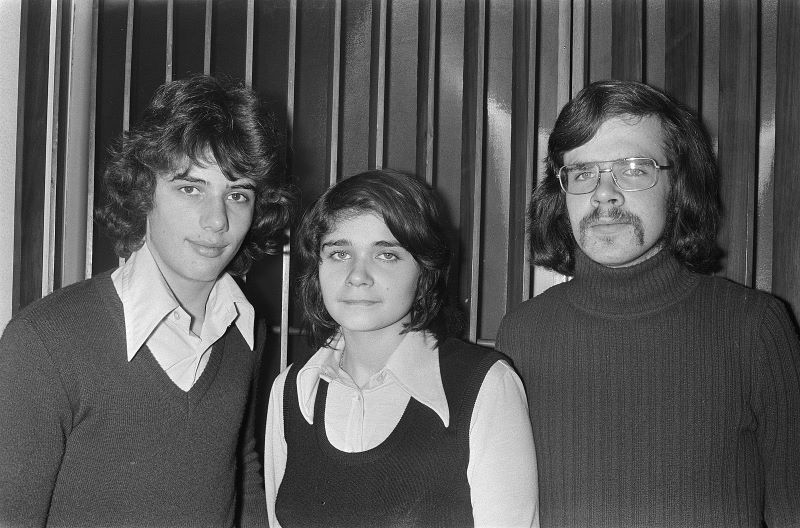

From left to right: Ronnie Berteling (ice hockey), Jacky Leenders (fencing/foil), Paul van der Sterren

In 1975 I received a scholarship from the Leo van der Kar Fund to finance a “training abroad”, an honor that had been bestowed upon Jan Timman a few years before. The training abroad turned out to be a two-week internship at the Central Chess Club in Moscow.

For a nineteen-year-old who knew Eastern Europe, hidden as it was behind the Iron Curtain, solely from newspapers and chess magazines, it was undoubtedly a great adventure with many stories to tell. But for the moment I will focus on the beginning.

A journey of this kind started in The Hague back then. You had to go to the Soviet Embassy to apply for a visa. For me, and no doubt for many before and after me, it was a brutal introduction to the power, but also the powerlessness, of the phenomenon called bureaucracy.

I duly present myself at the counter, and after not too long I find myself facing a Russian man who doesn’t seem that unfriendly and communicates in English. So far, so good. But then, he examines the documents I’ve been given, including the official invitation from the Central Chess Club in Moscow, and, in a reserved tone, he remarks that an official invitation from the Central Chess Club is missing. Surprised, thinking that he must have overlooked it, I protest and tell him it’s right there, it’s included. But no, somewhere in the document the year is wrong, or a comma misplaced, I really don’t remember, but the man is unyielding, and, unfortunately, he can’t grant me a visa.

Dazed by incomprehension, I leave the building, stagger to the train station, and board the train to Amsterdam, which is where I wake up again. I call Euwe and ask him “Am I crazy or are they?” I don’t even think about the trip to Moscow anymore. Euwe says he’ll see what he can do, starting with a call to Moscow. A few days later he calls me back: he has talked to Botvinnik. The visa is ready. I go to The Hague again, this time not by my inexperienced and naive self, but accompanied by Ineke Bakker, who was the head of the KNSB bureau at the time and also secretary-general of FIDE (of which Euwe was the president). And indeed, the visa is there.

The bureaucrats had their little fun, but now that a high-level order has been issued that playtime is over, and that they are face to face with somebody who doesn’t accept ‘no’ for an answer, they immediately give in.

It made it clear to me how powerful Euwe was, the enormous size of his network.

In our relationship this was the second significant learning moment for me. Yes, forces like the Soviet bureaucracy are strong but they also have their Achilles’ heel. About ten years later, I found myself once again at the Soviet Embassy in The Hague fort he same reason, facing another gloomy guy. But this time, I had the right attitude. Moaning? Wrong comma? Njet? Okay, in that case I will contact your superiors in Moscow rightaway. And that’s what I said. And this time the response was: yes, of course, sir. Everything is in order.

With thanks to Euwe.

Translation: Arnoud Jansen