In 1993 brak er zwaar weer uit boven de FIDE. En het jaar leek nog wel zo mooi te beginnen. In januari had Nigel Short zich geplaatst voor de match om het wereldkampioenschap door in San Lorenzo del Escorial Jan Timman te verslaan.

Eindelijk eens iets anders dan de tweekampen Karpov-Kasparov. Hoewel Kasparov op de vraag wie hij verwachtte als winnaar van de kandidatenmatches antwoordde: “It will be Short, and it will be short”, keken velen toch naar de tweekamp uit.

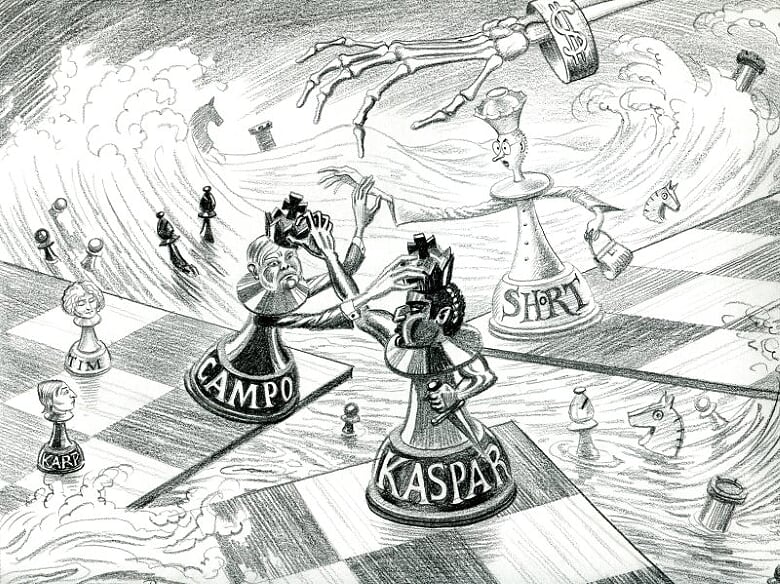

Er kon op de organisatie van de match geboden worden en uiteraard waren de ogen op Engeland gericht. Manchester bleek bereid het meest in de buidel te tasten en dat was het dan zou je zeggen. Niet dus. Short en Kasparov vonden dat de FIDE in de persoon van voorzitter Campomanes onvoldoende zijn best had gedaan om een hoger prijzengeld te regelen. Bovendien verweten ze hem dat hij niet met hen had overlegd over het aanvaarden van het bod uit Manchester, zoals de regels voorschreven. Ook het feit dat twintig procent van het prijzengeld naar de FIDE ging riep irritatie op. Daarop besloten Short en Kasparov een eigen organisatie op te richten, de Professional Chess Association (PCA), en de match zelf te organiseren.

Nog voor de tweekamp begon gaf Short toe de PCA te hebben opgericht voor het geld. Het prijzengeld van de match in eigen beheer lag een miljoen dollar hoger. In een interview met Jeroen van den Berg zei hij: “Voor veel mensen is dat misschien niet veel, maar voor mij wel.” Of de PCA op dat moment echt toekomst had durfde hij niet te zeggen. “Het is (…) mogelijk dat de PCA in haar gehele bestaan slechts één evenement organiseert, namelijk de match Kasparov-Short.”

De voorspelling dat de PCA geen toekomst had kwam aardig uit. Er volgde weliswaar een cyclus om de wereldtitel, maar in 1996 was het al weer afgelopen toen sponsor Intel ermee ophield.

De FIDE stond nu voor de vraag wat te doen. Om te beginnen raakte Kasparov zijn wereldtitel kwijt en verloren beide spelers hun rating. Dat laatste trouwens tot irritatie van de andere topspelers. Daarna werd er een vervangende tweekamp gepland tussen Jan Timman en Anatoli Karpov. Daarover kunt u bij een andere tekening meer lezen.

De match Short-Kasparov vond niet in Manchester plaats maar wel in Engeland. Er werd gespeeld in het klassieke Savoy Theatre in hartje Londen. De belangstelling van pers en publiek was geweldig en gehoopt werd dat het schaken in Engeland een grote stimulans zou krijgen. Door het verloop van de match kwam dat niet uit. De voorspelling van Kasparov bleek accuraat: na twintig van de vierentwintig partijen was het afgelopen: 12½-7½ voor de titelhouder.

Toch vraag je je af hoe het zou zijn gegaan als Short in de eerste partij niet in duidelijk betere stelling de tijd had overschreden. Nu stortte hij bijna onmiddellijk in. Na vier partijen stond het al 3½-½ voor Kasparov en was de match in feite beslist.

En de FIDE, was die de lachende derde? Niet helemaal. Het rond krijgen van de wedstrijd Timman-Karpov kostte heel veel moeite, de geldschieters stonden bepaald niet in de rij en voorzitter Campomanes had zijn hand overspeeld met vage beloftes. De stormen in de schaakwereld bleven nog even. (MbdW)

Kasparov-Short 1993

In 1993, FIDE was in stormy weather, even though the year had started quite well. In January, Nigel Short had qualified for the World Championship Final by beating Jan Timman in San Lorenzo del Escorial.

Finally we were going to get something different than the endless Karpov-Kasparov matches. Although Kasparov’s reaction to the question who he expected to be the winner of the Candidates Matches was, ‘It will be Short, and it will be short’, still many chess fans looked forward to this match.

Cities were invited to make bids for the organization of the match, and naturally all eyes focussed on England. It turned out that Manchester was prepared to dig deepest in its pockets, and you might have thought it was settled – but it wasn’t. Short and Kasparov thought that FIDE, in the person of chairman Campomanes, had not done its utmost to arrange higher prize funds. Moreover, they blamed him for not conferring with them about the acceptance of the Manchester bid, as the regulations prescribed. The players were also irritated by the fact that twenty percent of the prize money would go to FIDE. Next, Short and Kasparov decided to establish their own organization, the Professional Chess Association (PCA), and organize the match themselves.

Even before the match started, Short admitted to have founded the PCA for the money. The prize fund of their own match was a million dollars higher. In an interview with Jeroen van den Berg, he said: ‘This may not be much for many people, but it is for me.’ Whether the PCA had any real future, he couldn’t say. ‘It is (…) possible that the PCA will only organize one event in its entire existence, namely the Kasparov-Short match.’

The prediction that the PCA didn’t have a future proved correct. While the match was followed by a cycle for the world title, it was all over in 1996 when Intel stopped as a sponsor.

Now what was FIDE to do? To start with, Kasparov was stripped of his world title, and both players lost their ratings. The latter, by the way, caused irritation with other top players. Next, a substitute match was planned between Jan Timman and Anatoli Karpov. You can read more on that subject under a different cartoon in this series.

The Short-Kasparov match didn’t take place in Manchester, but it was played in England: in the classical Savoy Theatre in the heart of London. The interest of the press and the public was great, and it was hoped that chess in England would be given a big boost. However, this didn’t happen, due to the way the match went. Kasparov’s prediction turned out to be accurate: after twenty games out of a total of twenty-four, it was over: 12½-7½ for the title holder.

Still, you can’t help but wonder how the match would have turned out if Short hadn’t forfeited on time in a clearly better position in the first game. As things went, he collapsed

almost immediately. After four games, Kasparov was already leading by 3½-½, and the match was all but decided.

So, was FIDE the third party laughing now? Not really. It took a lot of effort to get the Timman-Karpov match off the ground, the sponsors were not exactly queueing up, and chairman Campomanes had overplayed his hand with vague promises. The storms in the chess world hadn’t subsided yet. (MbdW)