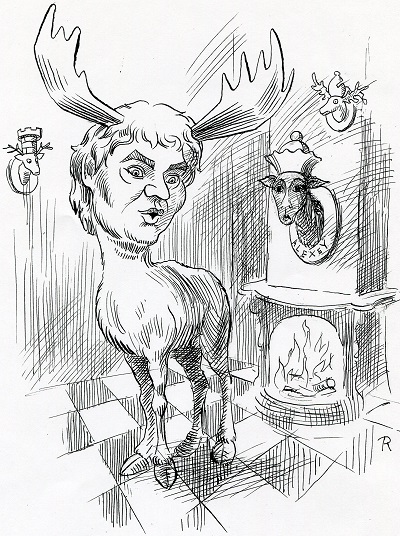

Over Alexej Sjirov valt veel te schrijven. Over zijn fantastische partijen (zie zijn boek Fire on Board I en II), over zijn relaties met diverse schaaksters, over zijn leven als schakende bohémien, maar vooral over zijn vele successen. Hier wil ik het hebben over een trofee die in het bezit is van het Max Euwe Centrum, de Trofeo a la Combatividad Linares 1993.

De in 2016 overleden journalist Jules Welling schonk het MEC een verzameling schaakcuriosa, waaronder deze beker. Toen Jules in 1993 bij het supertoernooi in Linares arriveerde had Sjirov net twee harde nederlagen moeten incasseren. Jules bood Alexej ’s avonds een drankje aan in de bar van het hotel waar gespeeld werd. Sjirov won de volgende dag en schreef de overwinning toe aan hun drankgelag, een traditie was geboren. Sjirov eindigde uiteindelijk als vierde, maar hij kreeg van Diaro Jaén de genoemde grote trofee.

In Jules Wellings verhalenbundel Grootmeesterverhalen, 30 jaar topschaak staan de volgende passages over deze trofee:

Na het feest kwam Alexej naar mijn tafeltje en zette de trofee voor me neer. “Die is voor jou,” zei hij eenvoudig. Ik was volledig verrast. “Dat kan ik niet aannemen, Alexej,” stamelde ik. “Jawel, hij is echt voor jou,” herhaalde hij. “Deze trofee wordt een ervaring voor je. Let op mijn woorden. ”Ik wist niet waarop hij doelde, maar op de een of andere manier voelde ik me trots. De volgende morgen pakte ik mijn spullen voor de terugreis naar Nederland, maar de trofee van Alexej kon niet in mijn koffers, omdat die eenvoudig te groot was. Ik moest hem als handbagage meezeulen. Op het station ontmoette ik Alexej weer. Ik wilde hem zijn prijs teruggeven, maar daar wilde hij niets van weten. “Je hebt hem echt verdiend,” zei hij. “En hij levert je een onvergetelijke ervaring op. Dat verzeker ik je.”

Zodra de trein zich in beweging had gezet, kwamen er allerhande passagiers op mij af om mij om een handtekening te vragen. “Maar dat is mijn trofee helemaal niet,” legde ik naar waarheid uit. “Ik heb hem van een vriend gekregen, die hem gewonnen heeft. Die zit hier ook ergens in de trein.” De passagiers geloofden me niet. “U bent een echte sportman, maar u hoeft niet zo bescheiden te zijn. Mag ik toch een handtekening van u?” vroeg een passagier.

Ook op het Madrileense vliegveld Barajas ontkwam Jules niet aan handtekeningenjagers en op Schiphol en in de trein van Amsterdam naar Geldrop dezelfde ervaringen. Een schaakjournalist die een dag het leven van een gevierde topschaker mocht leiden. Dat Sjirov zelf een hele andere herinnering aan dit hele verhaal heeft, is bijzaak. Sommige verhalen zijn te mooi om ‘kapot te checken’. (ES)

In onze Digitale Nieuwsbrief van maart 2017 staat een uitgebreid artikel over ‘de trofee’.

Shirov’s trophy

A lot can be written about Alexei Shirov – about his fantastic games (see his books Fire on Board I and II), his relationships with various women chess players, and his life as a chess-playing bohemian, but mainly about his many successes. In this article I would like to tell you the story of a trophy that is in the possession of the Max Euwe Centre, the Trofeo a la Combatividad Linares 1993.

The Dutch journalist Jules Welling, who passed away in 2016, gave a collection of chess curiosa to the MEC, and this cup was among them. When Jules arrived at the super-tournament in Linares in 1993, Shirov had just had to swallow two tough defeats. That night, Jules offered Alexei a drink in the bar of the hotel where the event was held. Shirov won the next day, ascribed his victory to their drinking bout, and a tradition was born. Eventually, Shirov ended in fourth place, but he received the abovementioned big trophy from Diaro Jaén.

In Jules Welling’s collection Grootmeesterverhalen, 30 jaar topschaak (= Grandmaster stories, 30 years of top-level chess) we can read the following passages about this trophy:

‘After the party, Alexei came to my table and put the trophy down before me. “This is for you,” he simply said. I was completely astonished. “I can’t accept that, Alexei,” I stammered. “Yes, you can, it really is yours,” he repeated. “This trophy will be a real experience for you – mark my words.” I didn’t understand what he meant, but in some way or another, I felt proud. The following morning, I packed my things for the return trip to the Netherlands, but Alexei’s trophy was simply too big for my suitcase. I had to drag it along with me as hand-luggage. I met Alexei again at the station. I wanted to give him back his prize, but he wouldn’t have it. “You really deserve it,” he said. “And it will bring you an unforgettable experience, I assure you.”

As soon as the train moved off, all kinds of passengers came up to me to ask for my autograph. “But this isn’t my trophy,” I explained truthfully, “I got it from a friend, who won it. He’s sitting elsewhere on this train.” The passengers didn’t believe me. “You are a real sportsman, but you don’t have to be so modest. Can I have your autograph anyway?” one of the passengers asked.’

Also on the Barajas airport in Madrid, Jules couldn’t evade the autograph hunters, and at Schiphol and on the train from Amsterdam to his home town Geldrop he had the same experiences: a chess journalist got to lead the life of a celebrated top chess player for one day. Shirov had a completely different recollection of this entire story, but that is of minor importance. Some stories are too good to be checked to death. (ES)

In our Digital Newsletter of March 2017 Digitale Nieuwsbrief van maart 2017 there is an extensive article about ‘the trophy’ (in Dutch).